The City of Boulder’s Community Assistance Response and Engagement (CARE) program was launched to provide a non-police response to low-acuity behavioral health, human service and medical calls that did not present with safety concerns. CARE paired a licensed behavioral health clinician with a dedicated paramedic to respond to selected 911 calls where no violence, weapons or criminal activity were involved. The goal was to resolve crises safely in the community, reduce reliance on law enforcement and connect residents to care.

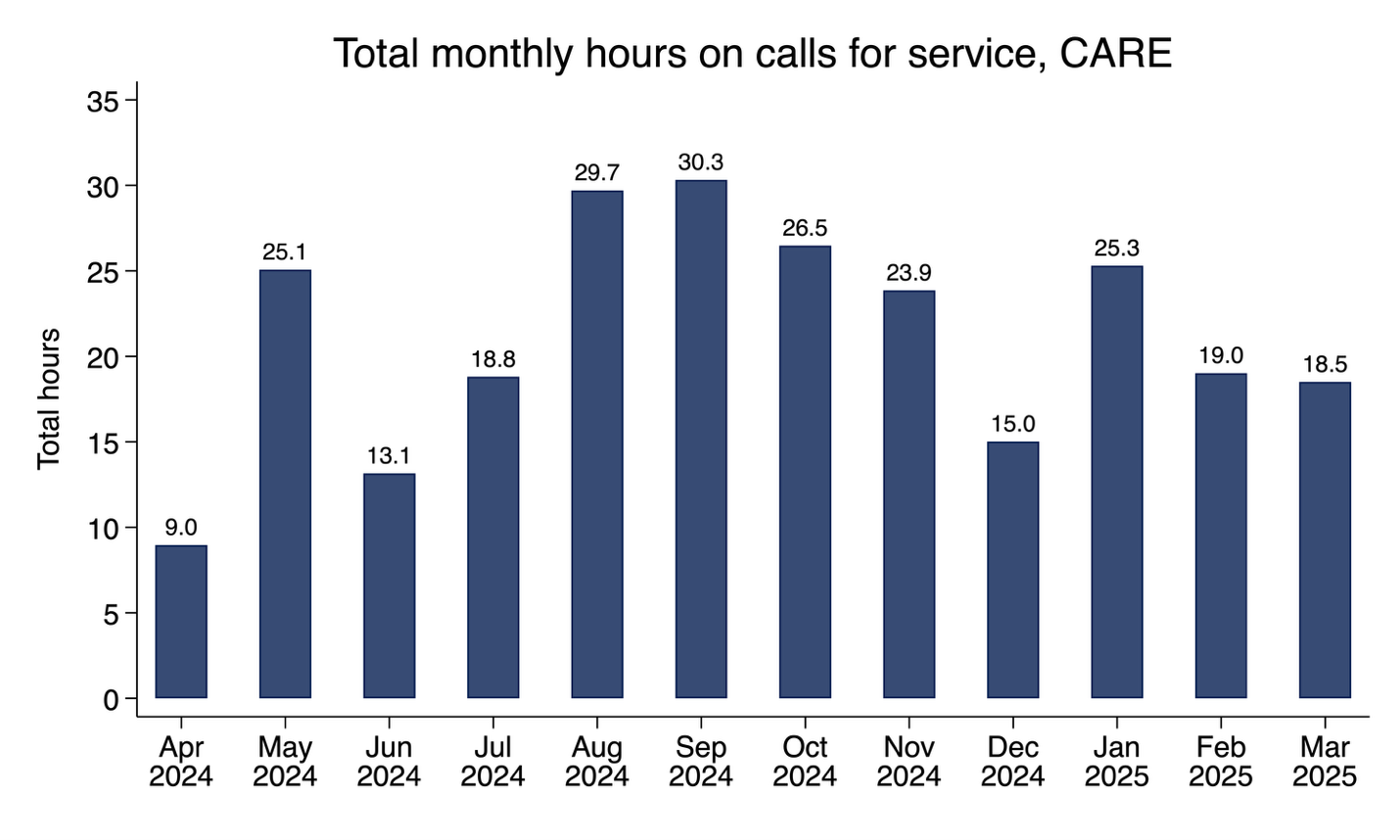

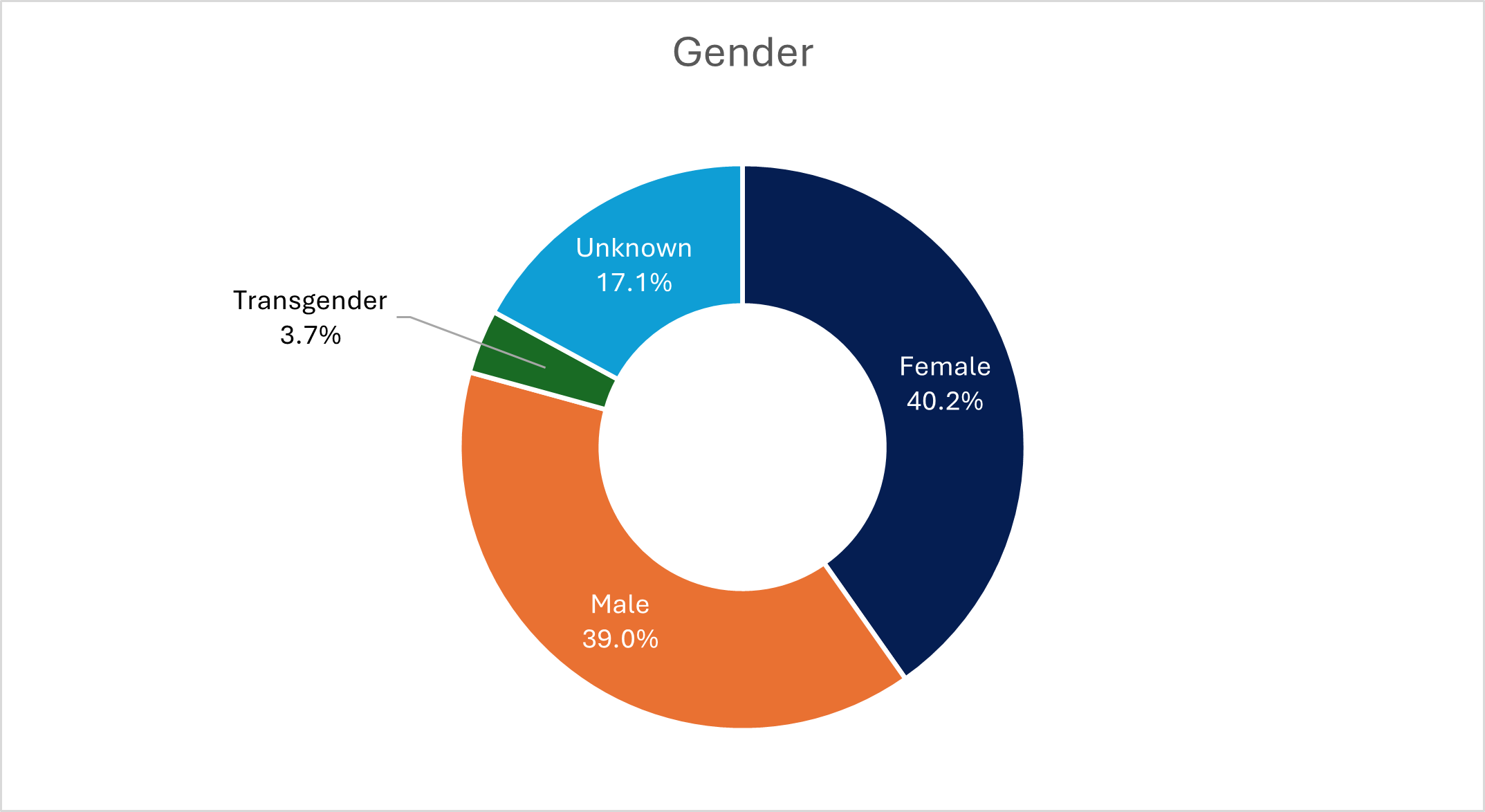

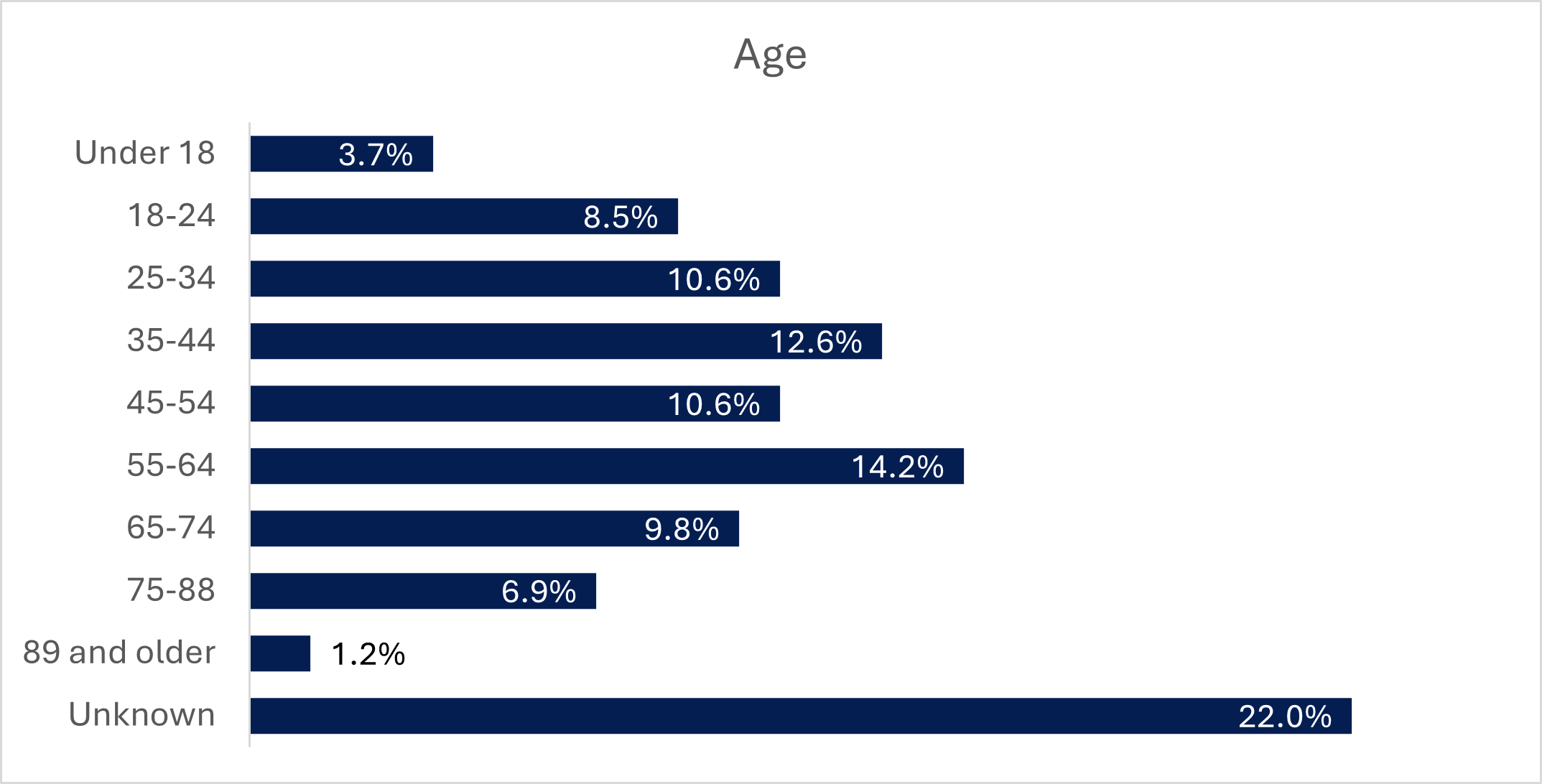

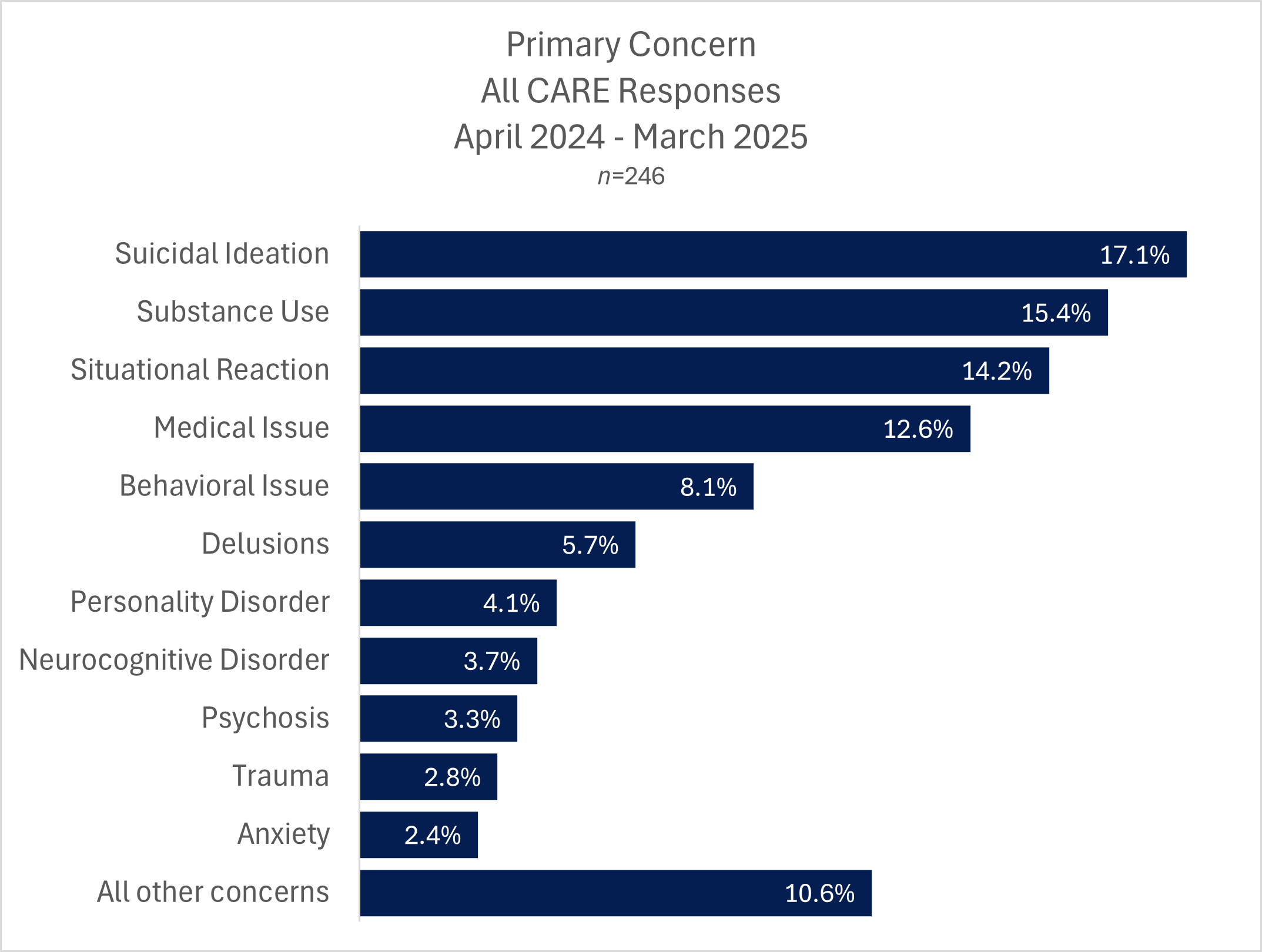

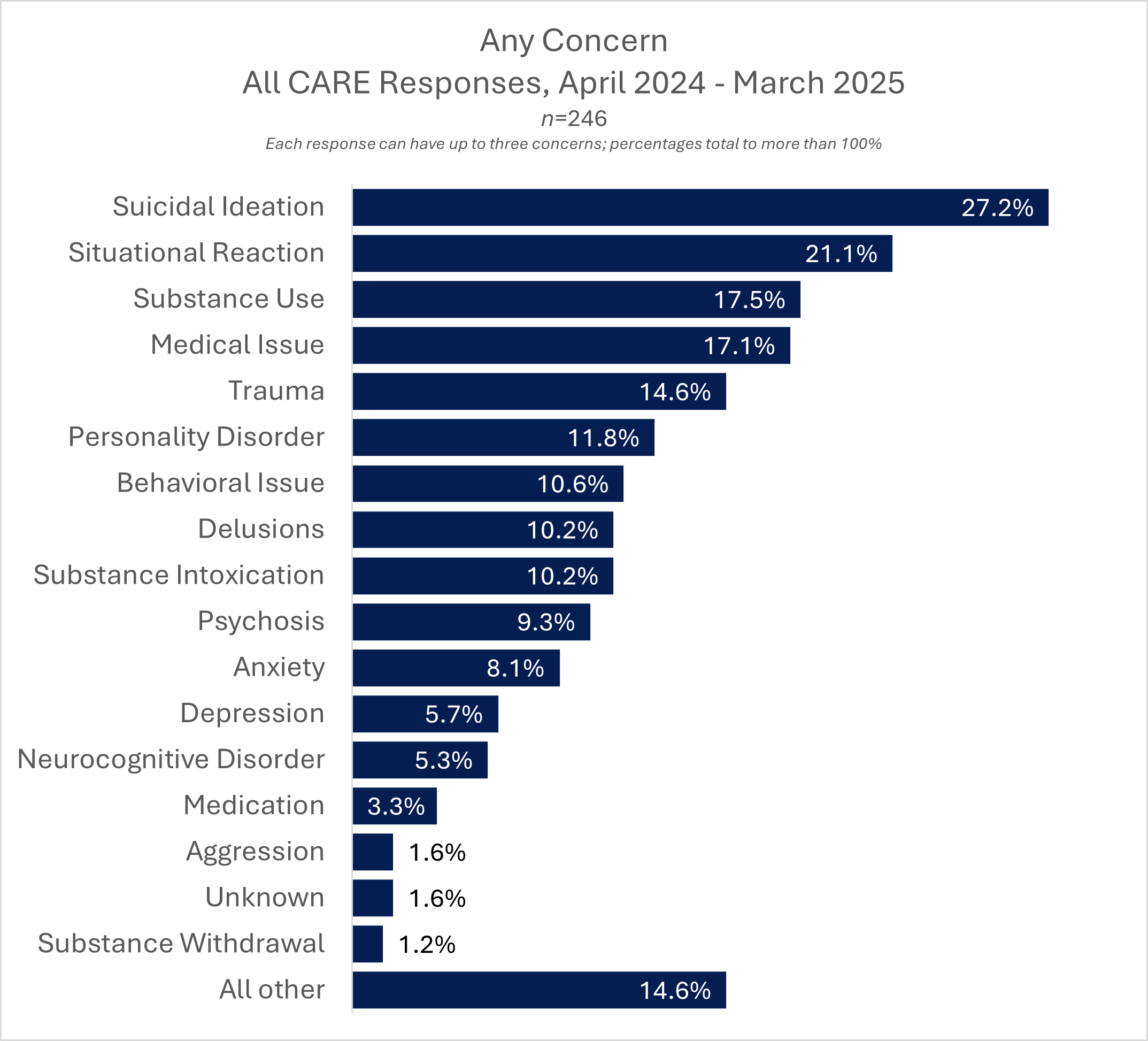

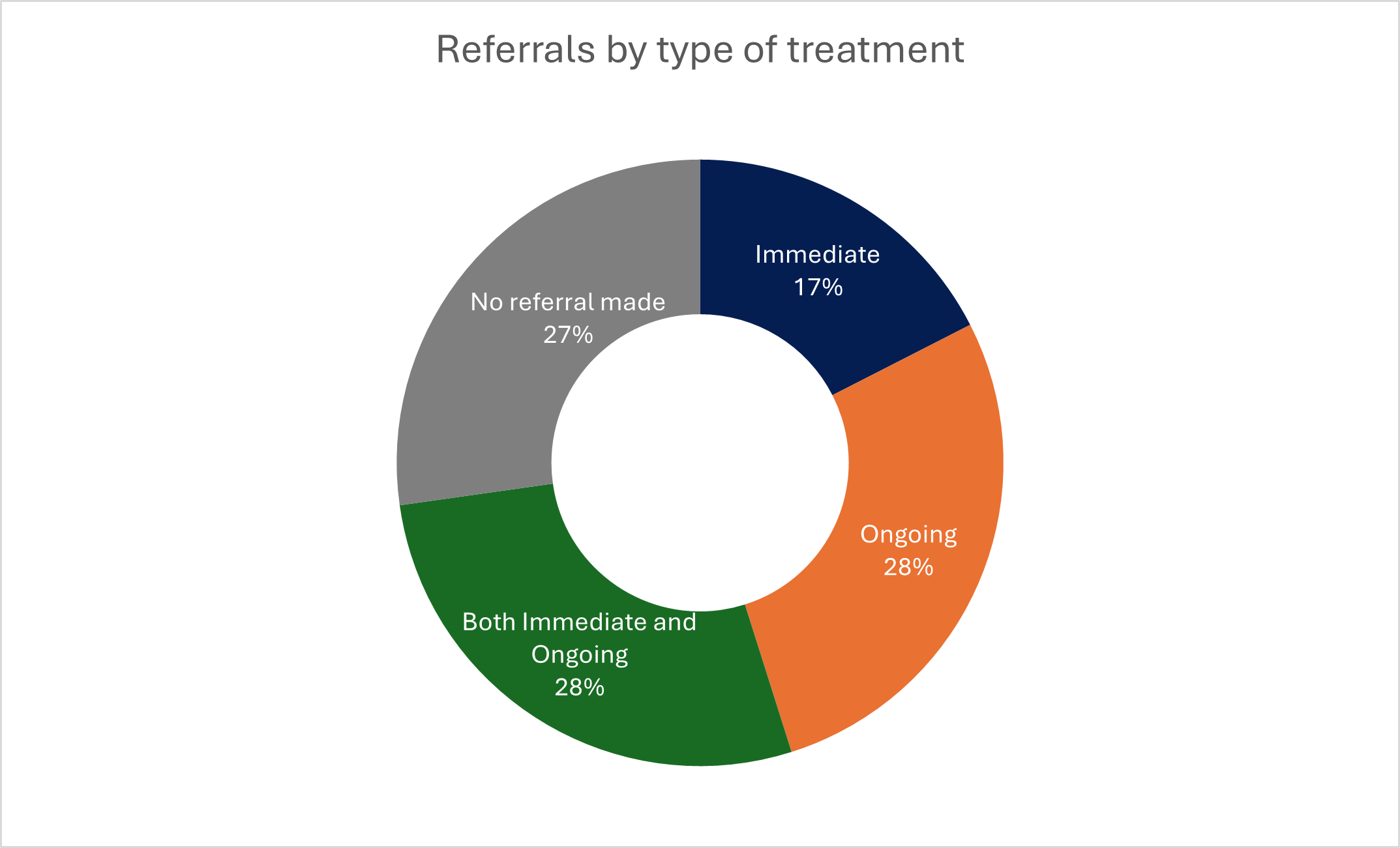

During its first full year of operation (April 2024 through March 2025), CARE completed 246 responses, serving at least 179 distinct individuals. Most people had only one contact with the team and the majority of incidents were resolved without the need for police or hospital transport. Over half of all CARE calls ended with the person remaining safely in the community, while nearly three-quarters of responses resulted in referrals to additional services such as case management, walk-in crisis care or medical treatment.

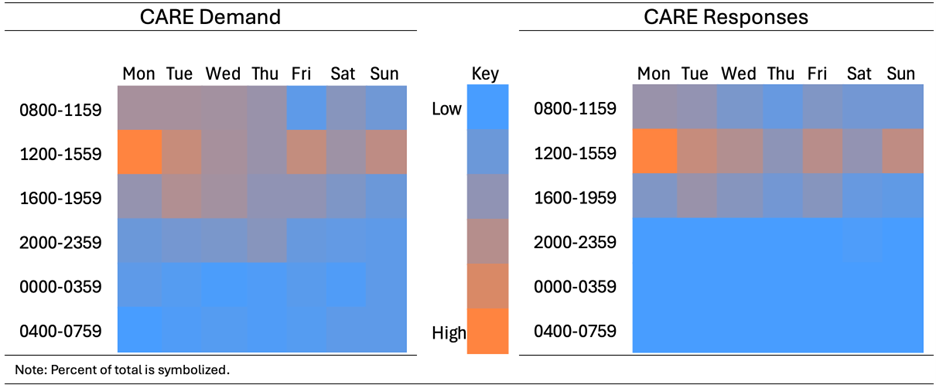

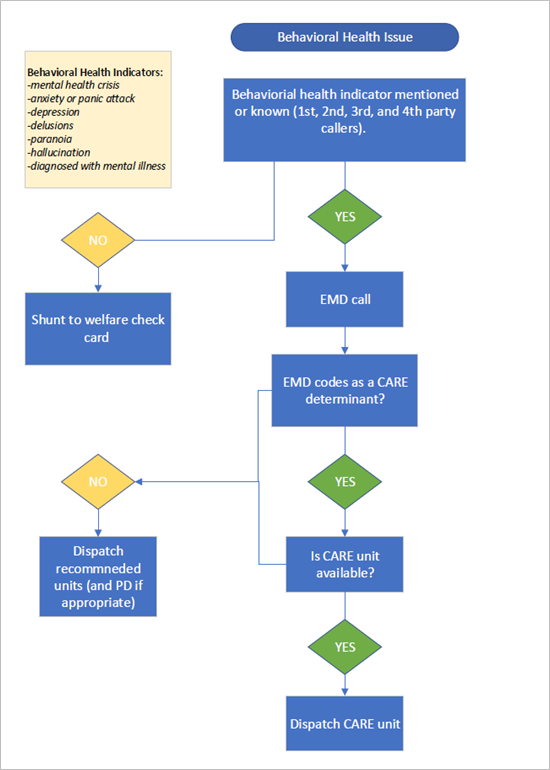

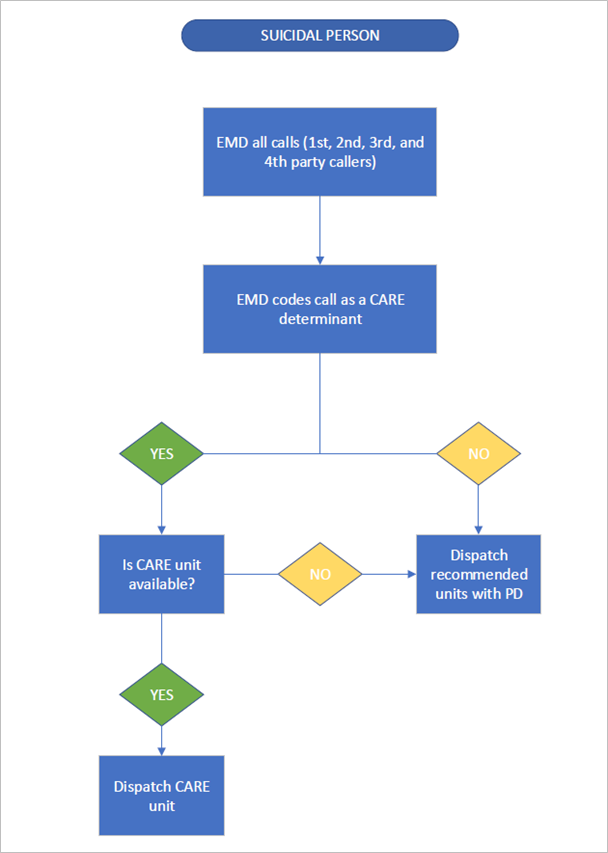

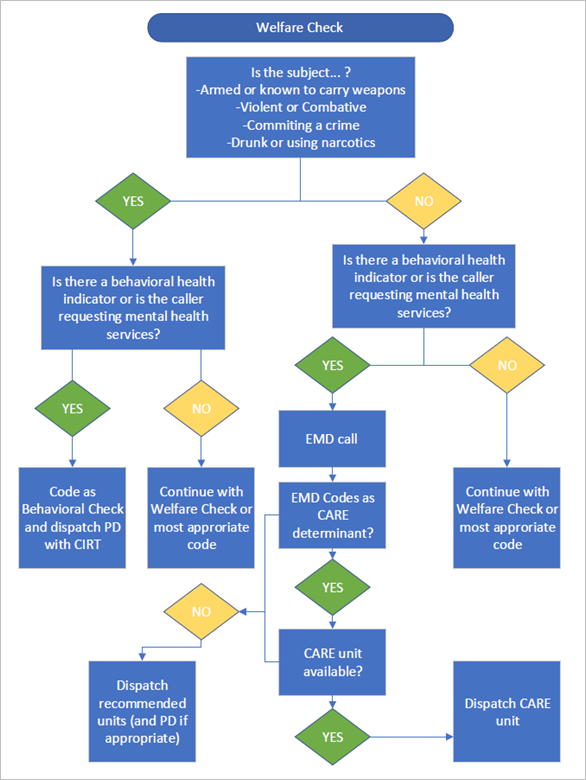

Strict dispatch protocols, designed to protect both responders and the public, limited the types of calls CARE could handle. This conservative approach led to low call volume and under-utilization of paramedics dedicated to the program. Staff interviews highlighted the value of CARE’s compassionate, health-focused approach—community members often engaged more readily with teams that did not include police—but also pointed to a need for more flexible dispatch criteria and better alignment across partner agencies.

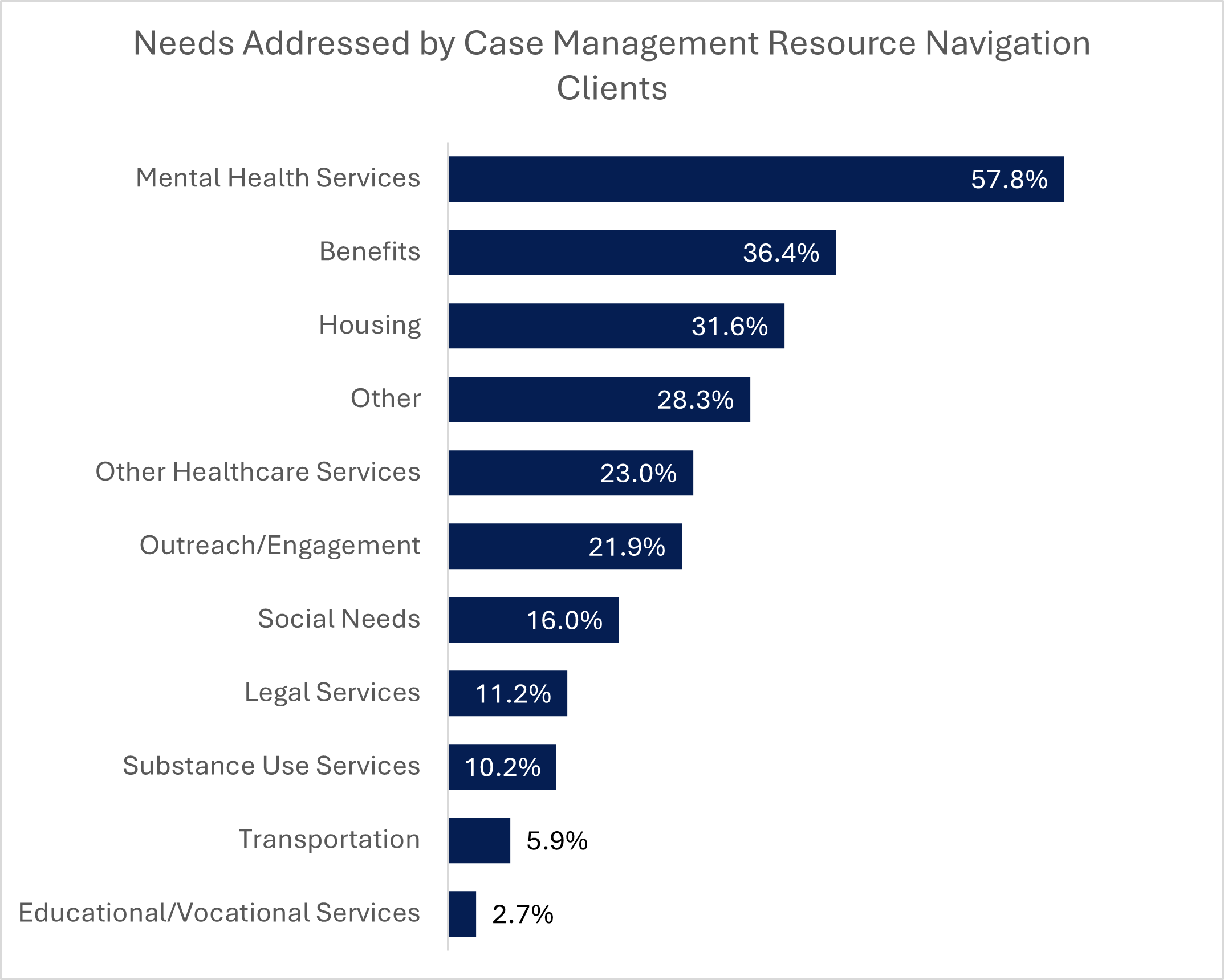

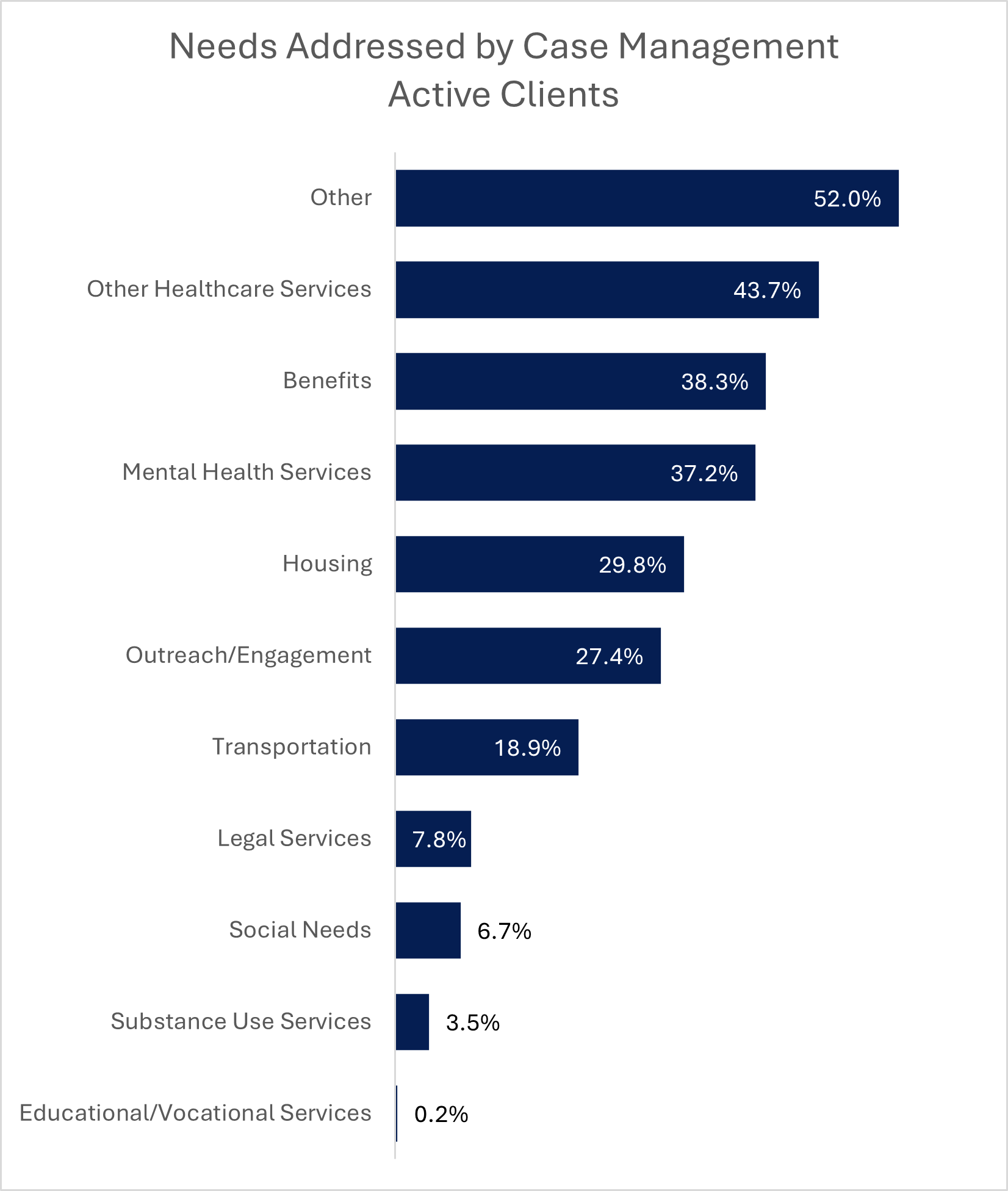

CARE’s clinical case management services emerged as a major strength. Case managers provided short-term, individualized support to help clients access benefits, treatment and housing. This ongoing engagement reduced the likelihood of repeated crises and strengthened collaboration among local service providers.

Overall, CARE proved that non-police crisis response can be safe, effective and well-received by the community. However, the number of calls appropriate for this model was relatively small. The findings suggest that Boulder should retain a non-police option as part of its broader behavioral health continuum, but dedicated paramedic staffing may not be the most efficient structure under current demand. Going forward, refining dispatch protocols, improving interagency coordination, exploring community paramedicine models with a broader scope of practice and expanding case management capacity will help Boulder build a more integrated and sustainable crisis response system.